We didn’t go to the store, we went to stand in line...

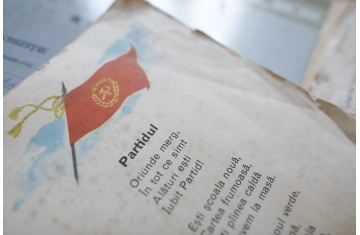

In my opinion, the line is a symbol of the ’80s. My parents told me that in the ’70s they found quite a lot of products at the market and in the restaurants. They seemed like stories from another world to me, because the reality of the ’80s was quite different. Nea Nicu [a popular nickname Nicolae Ceausescu had (Ol’ Nick) - Ed.] planned to become independent and to pay off all of Romania’s foreign debt. A joke had appeared, too: “Have you heard that Romania no longer has debts? Now we don’t really have anything left.”

The effect of this decision was to send most of the products for export, which left the shops empty. I remember the almost empty windows of the food stores. The only product that could be seen in the window, every day, was the box of Vietnamese shrimps. Another dry joke was the name of the poorest Arab in Romania: Ali Mentara, most of the food stores being called Alimentara [aliment=food -Ed.]). The food didn’t have time to get into the window. It suddenly appeared on the counter and was sold very quickly. In front of the empty shops, lines were formed, because they knew that it was a day for milk, meat or other products. The shops were closed until the product of the day appeared, to limit the agitation and arguments. After the product of the day appeared, the only thought was “will we get to the countertop in time to get some?”. We rarely stood quietly: “We’re sure to get it today, we’re in front of the line.” I also had surprises when I was in front and I didn’t get it, because each seller had a friend to whom he put it aside. When we got to the front, my mother used the secret weapon: she spoke Hungarian. At least in our neighbourhood most of the sellers and butchers were of Hungarian origin, and my mother used the advantage of knowing the language in order to get a better piece of meat or cheese.

These lines were the nightmare of my childhood and shortened my play time. Just when I was feeling the happiest, I heard “let’s go to the line and buy...” We didn’t go to the store, we went to stand in line. When I was young enough not to remember the story, but to hear it in my mother’s stories, we were walking around the neighbourhood and stopped in a line. From time to time, there were extra surprise products that came to the store. The first step was to hurry up to take our place in the line, and the second was to ask “what’s given today?”. I realised that we needed whatever was being sold and we would wait in line. As such I started screaming through tears: “You like standing in line! Every time you see a line, you stand there! All day long you stand in line!” The people around me laughed, but I didn’t understand why.

The pensioners were the masters of the lines. They knew the days when a certain food was scheduled to be sold and they appeared in front of the store a few hours in advance. Not everybody had old people at home, so they found a big line when they finished work at the factories around cities. Some of them would burst and start arguing, because not everyone who stood in line succeeded to buy something. Many times we stood in line without “catching” [getting anything -Ed.]. Grandma saved us in many situations. She was taking her stool from home and standing in line until our parents finished work at the factory, then our parents replaced her, and after we grew up, it was our turn.

Among the funniest lines was the one for milk. Some old people could not wait for hours in front of the store, but they left their net bags with bottles. Many times you could see a line made up of net bags with bottles and later people appeared behind the net bags. Probably the most famous joke about the line was the following: “A citizen sees a line in front of a store and comes near the first in the line:

- What is sold today?

- Nothing.

- What do you mean nothing? But why is everyone standing here?

- I don’t know, sir. I was walking down the street and fainted here. When I woke up everyone was behind me.

- And why don’t you go home, if nothing is sold here?

- Are you crazy? Now, when I am the first in line?"

At the end of the ’80s, the basic products were rationalised: bread, sugar, oil, flour. It was poverty equity that offered me shorter lines for a few products.

Cristi Tutunea, 46, Brasov